by admin | Oct 6, 2017 | ACA, IRS

Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), individuals are required to have health insurance while applicable large employers (ALEs) are required to offer health benefits to their full-time employees.

Reporting is required by employers with 50 or more full-time (or full-time equivalent) employees, insurers, or sponsors of self-funded health plans, on health coverage that is offered in order for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to verify that:

- Individuals have the required minimum essential coverage,

- Individuals who request premium tax credits are entitled to them, and

- ALEs are meeting their shared responsibility (play or pay) obligations.

2017 Draft Forms and Instructions

Draft instructions for both the 1094-B and 1095-B and the 1094-C and 1095-C were released, as were the draft forms for 1094-B, 1095-B, 1094-C, and 1095-C. There are no substantive changes in the forms or instructions between 2016 and 2017, beyond the further removal of now-expired forms of transition relief.

In past years the IRS provided relief to employers who make a good faith effort to comply with the information reporting requirements and determined that they will not be subject to penalties for failure to correctly or completely file. This did not apply to employers that fail to timely file or furnish a statement. For 2017, the IRS has unofficially indicated that the “good faith compliance efforts” relating to reporting requirements will not be extended. Employers should be ready to fully meet the reporting requirements in early 2018 with a high degree of accuracy. There is however relief for de minimis errors on Line 15 of the 1095-C.

The IRS also confirmed there is no code for the Form 1095-C, Line 16 to indicate an individual waived an offer of coverage. The IRS also kept the “plan start month” box as an optional item for 2017 reporting.

Employers must remember to provide all printed forms in landscape, not portrait.

When? Which Employers?

Reporting will be due early in 2018, based on coverage in 2017.

For calendar year 2017, Forms 1094-C, 1095-C, 1094-B, and 1095-B must be filed by February 28, 2018, or April 2, 2018, if filing electronically. Statements to employees must be furnished by January 31, 2018. In late 2016, a filing deadline was provided for forms due in early 2017, however it is unknown if that extension will be provided for forms due in early 2018. Until employers are told otherwise, they should plan on meeting the current deadlines.

All reporting will be for the 2017 calendar year, even for non-calendar year plans. The reporting requirements are in Sections 6055 and 6056 of the ACA.

By Danielle Capilla

Originally Published By United Benefit Advisors

by admin | Aug 31, 2017 | Benefit Management, Flexible Spending Accounts

A health flexible spending account (FSA) is a pre-tax account used to pay for out-of-pocket health care costs for a participant as well as a participant’s spouse and eligible dependents. Health FSAs are employer-established benefit plans and may be offered with other employer-provided benefits as part of a cafeteria plan. Self-employed individuals are not eligible for FSAs.

Even though a health FSA may be extended to any employee, employers should design their health FSAs so that participation is offered only to employees who are eligible to participate in the employer’s major medical plan. Generally, health FSAs must qualify as excepted benefits, which means other nonexcepted group health plan coverage must be available to the health FSA’s participants for the year through their employment. If a health FSA fails to qualify as an excepted benefit, then this could result in excise taxes of $100 per participant per day or other penalties.

Contributing to an FSA

Money is set aside from the employee’s paycheck before taxes are taken out and the employee may use the money to pay for eligible health care expenses during the plan year. The employer owns the account, but the employee contributes to the account and decides which medical expenses to pay with it.

At the beginning of the plan year, a participant must designate how much to contribute so the employer can deduct an amount every pay day in accordance with the annual election. A participant may contribute with a salary reduction agreement, which is a participant election to have an amount voluntarily withheld by the employer. A participant may change or revoke an election only if there is a change in employment or family status that is specified by the plan.

Per the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), FSAs are capped at $2,600 per year per employee. However, since a plan may have a lower annual limit threshold, employees are encouraged to review their Summary Plan Description (SPD) to find out the annual limit of their plan. A participant’s spouse can put $2,600 in an FSA with the spouse’s own employer. This applies even if both spouses participate in the same health FSA plan sponsored by the same employer.

Generally, employees must use the money in an FSA within the plan year or they lose the money left in the FSA account. However, employers may offer either a grace period of up to two and a half months following the plan year to use the money in the FSA account or allow a carryover of up to $500 per year to use in the following year.

By Danielle Capilla

Originally Published By United Benefit Advisors

by admin | Aug 29, 2017 | ACA, Health Plan Benchmarking

Small employers, those with fewer than 100 employees, have a reputation for not offering health insurance benefits that are competitive with larger employers, but new survey data from UBA’s Health Plan Survey reveals they are keeping pace with the average employer and, in fact, doing a better job of containing costs.

Small employers, those with fewer than 100 employees, have a reputation for not offering health insurance benefits that are competitive with larger employers, but new survey data from UBA’s Health Plan Survey reveals they are keeping pace with the average employer and, in fact, doing a better job of containing costs.

According to our new special report: “Small Businesses Keeping Pace with Nationwide Health Trends,” employees across all plan types pay an average of $3,378 toward annual health insurance benefits, with their employer picking up the rest of the total cost of $9,727. Among small groups, employees pay $3,557, with their employer picking up the balance of $9,474 – only a 5.3 percent difference.

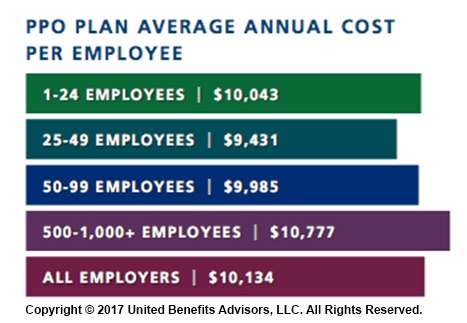

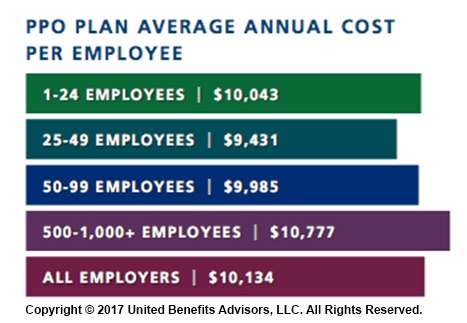

When looking at total average annual cost per employees for PPO plans, small businesses actually cut a better deal even compared to their largest counterparts—their costs are generally below average—and the same holds true for small businesses offering HMO and CDHP plans. (Keep in mind that relief such as grandmothering and the PACE Act helped many of these small groups stay in pre-ACA plans at better rates, unlike their larger counterparts.)

Think small businesses are cutting coverage to drive these bargains? Compared to the nations very largest groups, that may be true, but compared to average employers, small groups are highly competitive.

By Bill Olson

Originally Published By United Benefit Advisors

by admin | May 1, 2017 | ACA, Benefit Management, Group Benefit Plans, Human Resources

On April 18, 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published its final rule regarding Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) market stabilization.

On April 18, 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) published its final rule regarding Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) market stabilization.

The rule amends standards relating to special enrollment periods, guaranteed availability, and the timing of the annual open enrollment period in the individual market for the 2018 plan year, standards related to network adequacy and essential community providers for qualified health plans, and the rules around actuarial value requirements.

The proposed changes primarily affect the individual market. However, to the extent that employers have fully insured plans, some of the proposed changes will affect those employers’ plans because the changes affect standards that apply to issuers.

The regulations are effective on June 17, 2017.

Among other things impacting group plans, the rule provided clarifications to the scope of the guaranteed availability policy regarding unpaid premiums. The guaranteed availability provisions require health insurance issuers offering non-grandfathered coverage in the individual or group market to offer coverage to and accept every individual and employer that applies for such coverage unless an exception applies. Individuals and employers must usually pay the first month’s premium to activate coverage.

CMS previously interpreted the guaranteed availability provisions so that a consumer would be allowed to purchase coverage under a different product without having to pay past due premiums. Further, if an individual tried to renew coverage in the same product with the same issuer, then the issuer could apply the enrollee’s upcoming premium payments to prior non-payments.

Under the final rule and as permitted by state law, an issuer may apply the initial premium payment to any past-due premium amounts owed to that issuer. If the issuer is part of a controlled group, the issuer may apply the initial premium payment to any past-due premium amounts owed to any other issuer that is a member of that controlled group, for coverage in the 12-month period preceding the effective date of the new coverage.

Practically speaking, when an individual or employer makes payment in the amount required to trigger coverage and the issuer lawfully credits all or part of that amount to past-due premiums, the issuer will determine that the consumer made insufficient initial payment for new coverage.

This policy applies both inside and outside of the Exchanges in the individual, small group, and large group markets, and during applicable open enrollment or special enrollment periods.

This policy does not permit a different issuer (other than one in the same controlled group as the issuer to which past-due premiums are owed) to condition new coverage on payment of past-due premiums or permit any issuer to condition new coverage on payment of past-due premiums by any individual other than the person contractually responsible for the payment of premiums.

Issuers adopting this premium payment policy, as well as any issuers that do not adopt the policy but are within an adopting issuer’s controlled group, must clearly describe the consequences of non-payment on future enrollment in all paper and electronic forms of their enrollment application materials and any notice that is provided regarding premium non-payment.

By Danielle Capilla, Originally Published By United Benefit Advisors

by admin | Apr 28, 2017 | ACA, Benefit Management, Compliance

While the health care affordability crisis has become so significant, questions still linger—will private exchanges become a viable solution for employers and payers, and will they will continue to grow? Back in 2015, Accenture estimated that 40 million people would be enrolled in private exchange programs by 2018; the way we see this model’s growth today doesn’t speak to that. So, what is preventing them from taking off as they were initially predicted? We rounded up a few reasons why the private exchange model’s growth may be delayed, or coming to a halt.

While the health care affordability crisis has become so significant, questions still linger—will private exchanges become a viable solution for employers and payers, and will they will continue to grow? Back in 2015, Accenture estimated that 40 million people would be enrolled in private exchange programs by 2018; the way we see this model’s growth today doesn’t speak to that. So, what is preventing them from taking off as they were initially predicted? We rounded up a few reasons why the private exchange model’s growth may be delayed, or coming to a halt.

They Are Not Easy to Deploy

There is a reason why customized benefits technology was the talk of the town over the last two years; it takes very little work up-front to customize your onboarding process. Alternatively, private exchange programs don’t hold the same reputation. The online platform selection, build, and test alone can get you three to six months into the weeds. Underwriting, which includes an analysis of the population’s demographics, family content, claims history, industry, and geographic location, will need to take place before obtaining plan pricing if you are a company of a certain size. Moreover, employee education can make up a significant time cost, as a lack of understanding and too many options can lead to an inevitable resistance to changing health plans. Using a broker, or an advisor, for this transition will prove a valuable asset should you choose to go this route.

A Lack of Education and a Relative Unfamiliarity Revolves Around Private Exchanges

Employers would rather spend their time running their businesses than understanding the distinctions between defined contribution and defined benefits models, let alone the true value proposition of private exchanges. With the ever-changing political landscape, employers are met with an additional challenge and are understandably concerned about the tax and legal implications of making these potential changes. They also worry that, because private exchanges are so new, they haven’t undergone proper testing to determine their ability to succeed, and early adoption of this model has yet to secure a favorable cost-benefit analysis that would encourage employers to convert to this new program.

They May Not Be Addressing All Key Employer and Payer Concerns

We see four key concerns stemming from employers and payers:

- Maintaining competitive benefits: Exceptional benefits have become a popular way for employers to differentiate themselves in recruiting and retaining top talent. What’s the irony? More options to choose from across providers and plans means employees lose access to group rates and can ultimately pay more, making certain benefits less. As millennials make up more of today’s workforce and continue to redefine the value they put behind benefits, many employers fear they’ll lose their competitive advantage with private exchanges when looking to recruit and retain new team members.

- Inexperienced private exchange administrators: Because many organizations have limited experience with private exchanges, they need an expert who can provide expertise and customer support for both them and their employees. Some administrators may not be up to snuff with what their employees need and expect.

- Margin compression: In the eyes of informed payers, multi-carrier exchanges not only commoditize health coverage, but perpetuate a concern that they could lead to higher fees. Furthermore, payers may have to go as far as pitching in for an individual brokerage commission on what was formerly a group sale.

- Disintermediation: Private exchanges essentially remove payer influence over employers. Bargaining power shifts from payers to employers and transfers a majority of the financial burden from these decisions back onto the payer.

It Potentially Serves as Only a Temporary Solution to Rising Health Care Costs

Although private exchanges help employers limit what they pay for health benefits, they have yet to be linked to controlling health care costs. Some experts argue that the increased bargaining power of employers forces insurers to be more competitive with their pricing, but there is a reduced incentive for employers to ask for those lower prices when providing multiple plans to payers. Instead, payers are left with the decision to educate themselves on the value of each plan. With premiums for family coverage continuing to rise year-over-year—faster than inflation, according to Forbes back in 2015—it seems private exchanges may only be a band-aid to an increasingly worrisome health care landscape.

Thus, at the end of it all, change is hard. Shifting payers’, employers’, and ultimately the market’s perspective on the projected long-term success of private exchanges will be difficult. But, if the market is essentially rejecting the model, shouldn’t we be paying attention?

By Paul Rooney, Originally Published By United Benefit Advisors