by admin | Sep 6, 2017 | Compliance, HIPAA, Human Resources

When it comes to Employee Assistance Programs, confidentiality is a concern for both employers and employees. As an employer, it is helpful to understand the terms and processes your EAP uses to keep information confidential and ensure that your employees and your workplace are safe.

When it comes to Employee Assistance Programs, confidentiality is a concern for both employers and employees. As an employer, it is helpful to understand the terms and processes your EAP uses to keep information confidential and ensure that your employees and your workplace are safe.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) rules apply to EAPs and their affiliate providers. All information that is obtained during an EAP session is maintained in confidential files. The information remains confidential except in the following circumstances:

- An employee/client provides written permission/consent for the release of specific information. This can be done using a Consent to Inform or Release of Information form.

- The life or safety of the client or others is seriously threatened.

- Child abuse has occurred.

- EAP records are the subject of a court order (subpoena).

- Other disclosures required by applicable law.

Depending on the situation, an employee may use EAP services through a self-referral, guided-referral or mandated-referral

Voluntary or self-referrals are the most common. When an employee seeks EAP services voluntarily, all of the employee’s information, including whether he or she contacted the EAP or not, is confidential and cannot be released without written permission.

Guided referrals are an opportunity for the employer to encourage the employee to use EAP services when the employer senses there is a problem that needs to be addressed. This may occur when the employer identifies an employee who may be having personal or work-related difficulties but it is not to the point of mandating that the employee use an EAP. In the case of guided referrals, information disclosed by the employee is still kept confidential.

Mandatory or formal referrals usually occur when substance abuse or other behaviors are impacting productivity or safety. An employer’s policy may allow for putting the employee on a performance improvement plan and may even include a “last chance” agreement that states what an employee must do in order to keep their job. In these cases, employees are mandated by the employer to contact the EAP and a Release of Information is signed so the EAP can exchange information with the employer about employee attendance, compliance and recommendations.

In some cases, it may be advised to send the employee for a Fitness for Duty Evaluation or similar assessment to determine the employee’s ability to physically or mentally perform essential job duties, or assess for a potential threat of violence. These evaluations are performed by specially trained professionals and will come with an additional cost. If the employee has provided written consent, limited information may be released to the employer regarding the results of these evaluations.

By Kathryn Schneider

Originally Published By United Benefit Advisors

by admin | Aug 24, 2017 | Benefit Management, COBRA, Compliance

The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) allows qualified beneficiaries who lose health benefits due to a qualifying event to continue group health benefits. The COBRA payment process is subject to various rules in terms of grace periods, notification, premium payment methods, and treatment of insignificant shortfalls.

Grace Periods

The initial premium payment is due 45 days after the qualified beneficiary elects COBRA. Premium payments must be made on time; otherwise, a plan may terminate COBRA coverage. Generally, subsequent premium payments are due on the first day of the month. However, under the COBRA grace period rules, premiums will still be considered timely if made within 30 days after the due date. The statutory grace period is a minimum 30-day period, but plans may allow qualified beneficiaries a longer grace period.

A COBRA premium payment is made when it is sent to the plan. Thus, if the qualified beneficiary mails a check, then the payment is made on the date the check was mailed. The plan administrators should look at the postmark date on the envelope to determine whether the payment was made on time. Qualified beneficiaries may use certified mail as evidence that the payment was made on time.

The 30-day grace period applies to subsequent premium payments and not to the initial premium payment. After the initial payment is made, the first 30-day grace period runs from the payment due date and not from the last day of the 45-day initial payment period.

If a COBRA payment has not been paid on its due date and a follow-up billing statement is sent with a new due date, then the plan risks establishing a new 30-day grace period that would begin from the new due date.

Notification

The plan administrator must notify the qualified beneficiary of the COBRA premium payment obligations in terms of how much to pay and when payments are due; however, the plan does not have to renotify the qualified beneficiary to make timely payments. Even though plans are not required to send billing statements each month, many plans send reminder statements to the qualified beneficiaries.

While the only requirement for plan administrators is to send an election notice detailing the plan’s premium deadlines, there are three circumstances under which written notices about COBRA premiums are necessary. First, if the COBRA premium changes, the plan administrator must notify the qualified beneficiary of the change. Second, if the qualified beneficiary made an insignificant shortfall premium payment, the plan administrator must provide notice of the insignificant shortfall unless the plan administrator chooses to ignore it. Last, if a plan administrator terminates a qualified beneficiary’s COBRA coverage for nonpayment or late payment, the plan administrator must provide a termination notice to the qualified beneficiary.

The plan administrator is not required to inform the qualified beneficiary when the premium payment is late. Thus, if a plan administrator does not receive a premium payment by the end of the grace period, then COBRA coverage may be terminated. The plan administrator is not required to send a notice of termination in that case because the COBRA coverage was not in effect. On the other hand, if the qualified beneficiary makes the initial COBRA premium payment and coverage is lost for failure to pay within the 30-day grace period, then the plan administrator must provide a notice of termination due to early termination of COBRA coverage.

By Danielle Capilla

Originally Published By United Benefit Advisors

by admin | Aug 15, 2017 | Compliance, Health & Wellness

Where to Start?

Where to Start?

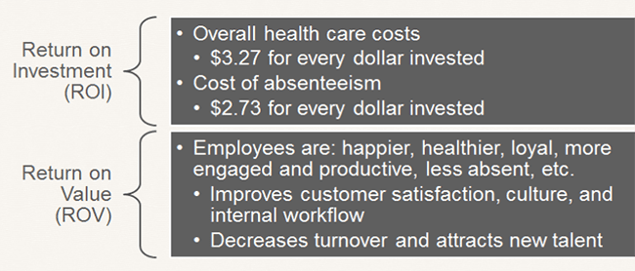

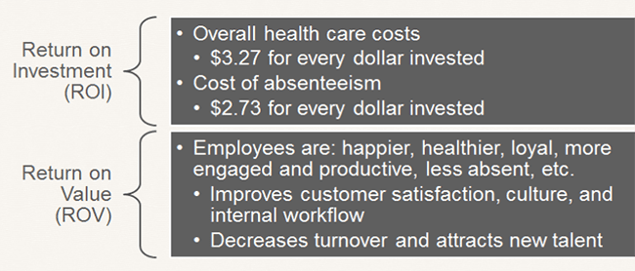

First, expand the usual scope of wellness activity to well-BEING. Include initiatives that support more than just physical fitness, such as career growth, social needs, financial health, and community involvement. By doing this you increase your chances of seeing a return on investment (ROI) and a return on value (ROV). Qualitative results of a successful program are just as valuable as seeing a financial impact of a healthier population.

Source: Katherine Baicker, David Cutler, and Zirui Song, “Workplace Wellness Programs Can Generate Savings,” Health Affairs, February 2010, 29(2): pp 304-311

To create a corporate culture of well-being and ensure the success of your program, there are a few important steps.

- Leadership Support: Programs with leadership support have the highest level of participation. Gain leadership support by having them participate in the programs, give recognition to involved employees, support employee communication, allow use of on-site space, approve of employees spending time on coordinating and facilitating initiatives, and define the budget. Even though you do not need a budget to be successful.

- Create a Committee or Designate a Champion: Do not take this on by yourself. Create a well-being committee, or identify a champion, to share the responsibility and necessary actions of coordinating a program.

- Strategic Plan: Create a three-year strategic plan with a mission statement, budget, realistic goals, and measurement tools. Creating a plan like this takes some work and coordination, but the benefits are significant. You can create a successful well-being program with little to no budget, but you need to know what your realistic goals are and have a plan to make them a reality.

- Tools and Resources: Gather and take advantage of available resources. Tools and resources from your broker and/or carrier can help make managing a program much easier. Additionally, an employee survey will help you focus your efforts and accommodate your employees’ immediate needs.

How to Remain Compliant?

As always, remaining compliant can be an unplanned burden on employers. Whether you have a wellness or well-being program, each has their own compliance considerations and requirements to be aware of. However, don’t let that stop your organization from taking action.

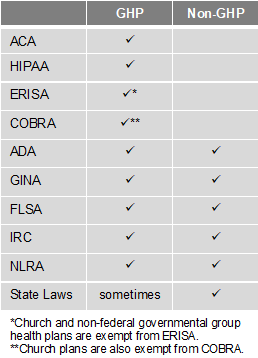

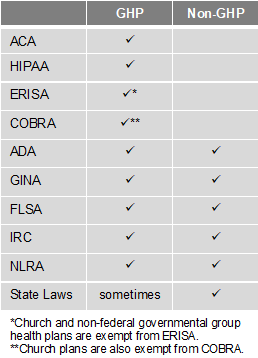

There are two types of programs – Group Health Plans (GHP) and Non-Group Health Plans (Non-GHP). The wellness regulations vary depending on the type of employer and whether the program is considered a GHP or Non-GHP.

Employers looking to avoid some of the compliance burden should design their well-being program to be a Non-GHP. Generally, a well-being program is Non-GHP if it is offered to all employees regardless of their enrollment in the employer’s health plan and does not provide or pay for “medical care.” For example, employees receive $100 for attending a class on nutrition. Here are some other tips to keep your well-being program Non-GHP:

- Financial: Do not pay for medical services (e.g., flu shots, biometric screenings, etc.) or provide medical care. Financial incentives or rewards must be taxed. Do not provide premium discounts or surcharges.

- Voluntary Participation: Include all employees, but do not mandate participation. Make activities easily accessible to those with disabilities or provide a reasonable alternative. Make the program participatory (i.e., educational, seminars, newsletters) rather than health-contingent (i.e., require participants to get BMI below 30 or keep cholesterol below 200). Do not penalize individuals for not participating.

- Health Information: Do not collect genetic data, including family medical history. Any medical records, or information obtained, must be kept confidential. Avoid Health Risk Assessments (i.e. health surveys) that provide advice and analysis with personalized coaching or ask questions about genetics/family medical history.

By Hope DeRocha

Originally Posted By www.ubabenefits.com

by admin | Jul 13, 2017 | COBRA, Compliance

The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) requires employers to offer covered employees who lose their health benefits due to a qualifying event to continue group health benefits for a limited time at the employee’s own cost. The length of the COBRA coverage period depends on the qualifying event and is usually 18 or 36 months. However, the COBRA coverage period may be extended under the following five circumstances:

The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) requires employers to offer covered employees who lose their health benefits due to a qualifying event to continue group health benefits for a limited time at the employee’s own cost. The length of the COBRA coverage period depends on the qualifying event and is usually 18 or 36 months. However, the COBRA coverage period may be extended under the following five circumstances:

- Multiple Qualifying Events

- Disability

- Extended Notice Rule

- Pre-Termination or Pre-Reduction Medicare Entitlement

- Employer Extension; Employer Bankruptcy

In this blog, we’ll examine the first circumstance above. For a detailed discussion of all the circumstances, request UBA’s Compliance Advisor, “Extension of Maximum COBRA Coverage Period”.

When determining the coverage period under multiple qualifying events, the maximum coverage period for a loss of coverage due to a termination of employment and reduction of hours is 18 months. The maximum coverage period may be extended to 36 months if a second qualifying event or multiple qualifying events occur within the initial 18 months of COBRA coverage from the first qualifying event. The coverage period runs from the start of the original 18-month coverage period.

The first qualifying event must be termination of employment or reduction of hours, but the second qualifying cannot be termination of employment, reduction of hours, or bankruptcy. In order to qualify for the extension, the second qualifying event must be the covered employee’s death, divorce, or child ceasing to be a dependent. In addition, the extension is only available if the second qualifying event would have caused a loss of coverage for the qualified beneficiary if it occurred first.

The extended 36-month period is only for spouses and dependent children. In order to qualify for extended coverage, a qualified beneficiary must have elected COBRA during the first qualifying event and must have been receiving COBRA coverage at the time of the second event. The qualified beneficiary must notify the plan administrator of the second qualifying event within 60 days after the event.

Example: Jim was terminated on June 3, 2017. Then, he got divorced on July 6, 2017. Jim was eligible for COBRA continuation coverage for 18 months after his termination of employment (the first qualifying event). However, his divorce (the second qualifying event) extended his COBRA continuation coverage to 36 months because it occurred within the initial 18 months of COBRA coverage from his termination (the first qualifying event).

The health plan should indicate when the coverage period begins. The plan may provide that that the plan administrator be notified when plan coverage is lost as opposed to when the qualifying event occurs. In that case, the 36-month coverage period would begin on the date coverage was lost.

By Danielle Capilla

Originally Posted By www.ubabenefits.com

by admin | Apr 28, 2017 | ACA, Benefit Management, Compliance

While the health care affordability crisis has become so significant, questions still linger—will private exchanges become a viable solution for employers and payers, and will they will continue to grow? Back in 2015, Accenture estimated that 40 million people would be enrolled in private exchange programs by 2018; the way we see this model’s growth today doesn’t speak to that. So, what is preventing them from taking off as they were initially predicted? We rounded up a few reasons why the private exchange model’s growth may be delayed, or coming to a halt.

While the health care affordability crisis has become so significant, questions still linger—will private exchanges become a viable solution for employers and payers, and will they will continue to grow? Back in 2015, Accenture estimated that 40 million people would be enrolled in private exchange programs by 2018; the way we see this model’s growth today doesn’t speak to that. So, what is preventing them from taking off as they were initially predicted? We rounded up a few reasons why the private exchange model’s growth may be delayed, or coming to a halt.

They Are Not Easy to Deploy

There is a reason why customized benefits technology was the talk of the town over the last two years; it takes very little work up-front to customize your onboarding process. Alternatively, private exchange programs don’t hold the same reputation. The online platform selection, build, and test alone can get you three to six months into the weeds. Underwriting, which includes an analysis of the population’s demographics, family content, claims history, industry, and geographic location, will need to take place before obtaining plan pricing if you are a company of a certain size. Moreover, employee education can make up a significant time cost, as a lack of understanding and too many options can lead to an inevitable resistance to changing health plans. Using a broker, or an advisor, for this transition will prove a valuable asset should you choose to go this route.

A Lack of Education and a Relative Unfamiliarity Revolves Around Private Exchanges

Employers would rather spend their time running their businesses than understanding the distinctions between defined contribution and defined benefits models, let alone the true value proposition of private exchanges. With the ever-changing political landscape, employers are met with an additional challenge and are understandably concerned about the tax and legal implications of making these potential changes. They also worry that, because private exchanges are so new, they haven’t undergone proper testing to determine their ability to succeed, and early adoption of this model has yet to secure a favorable cost-benefit analysis that would encourage employers to convert to this new program.

They May Not Be Addressing All Key Employer and Payer Concerns

We see four key concerns stemming from employers and payers:

- Maintaining competitive benefits: Exceptional benefits have become a popular way for employers to differentiate themselves in recruiting and retaining top talent. What’s the irony? More options to choose from across providers and plans means employees lose access to group rates and can ultimately pay more, making certain benefits less. As millennials make up more of today’s workforce and continue to redefine the value they put behind benefits, many employers fear they’ll lose their competitive advantage with private exchanges when looking to recruit and retain new team members.

- Inexperienced private exchange administrators: Because many organizations have limited experience with private exchanges, they need an expert who can provide expertise and customer support for both them and their employees. Some administrators may not be up to snuff with what their employees need and expect.

- Margin compression: In the eyes of informed payers, multi-carrier exchanges not only commoditize health coverage, but perpetuate a concern that they could lead to higher fees. Furthermore, payers may have to go as far as pitching in for an individual brokerage commission on what was formerly a group sale.

- Disintermediation: Private exchanges essentially remove payer influence over employers. Bargaining power shifts from payers to employers and transfers a majority of the financial burden from these decisions back onto the payer.

It Potentially Serves as Only a Temporary Solution to Rising Health Care Costs

Although private exchanges help employers limit what they pay for health benefits, they have yet to be linked to controlling health care costs. Some experts argue that the increased bargaining power of employers forces insurers to be more competitive with their pricing, but there is a reduced incentive for employers to ask for those lower prices when providing multiple plans to payers. Instead, payers are left with the decision to educate themselves on the value of each plan. With premiums for family coverage continuing to rise year-over-year—faster than inflation, according to Forbes back in 2015—it seems private exchanges may only be a band-aid to an increasingly worrisome health care landscape.

Thus, at the end of it all, change is hard. Shifting payers’, employers’, and ultimately the market’s perspective on the projected long-term success of private exchanges will be difficult. But, if the market is essentially rejecting the model, shouldn’t we be paying attention?

By Paul Rooney, Originally Published By United Benefit Advisors

by admin | Mar 22, 2017 | Benefit Management, Compliance, Human Resources, Medicare

Entities such as employers with group health plans that provide prescription drug coverage to individuals that are eligible for Medicare Part D have two major disclosure requirements that they must meet at least annually:

Entities such as employers with group health plans that provide prescription drug coverage to individuals that are eligible for Medicare Part D have two major disclosure requirements that they must meet at least annually:

- Provide annual written notice to all Medicare eligible individuals (employees, spouses, dependents, retirees, COBRA participants, etc.) who are covered under the prescription drug plan.

- Disclose to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) whether the coverage is “creditable prescription drug coverage.”

Because there is often ambiguity regarding who in a covered population is Medicare eligible, it is best practice for employers to provide the notice to all plan participants.

CMS provides guidance for disclosure of creditable coverage for both individuals and employers.

Who Must Disclose?

These disclosure requirements apply regardless of whether the plan is large or small, is self-funded or fully insured, or whether the group health plan pays primary or secondary to Medicare. Entities that provide prescription drug coverage through a group health plan must provide the disclosures. Group health plans include:

- Group health plans under ERISA, including health reimbursement arrangements (HRAs), dental and vision plans, certain cancer policies, and employee assistance plans (EAPs) if they provide medical care

- Group health plans sponsored for employees or retirees by a multiple employer welfare arrangement (MEWA)

- Qualified prescription drug plans

Health flexible spending accounts (FSAs), Archer medical savings accounts, and health savings accounts (HSAs) do not have disclosure requirements. In contrast, the high deductible health plan (HDHP) offered in conjunction with the HSA would have disclosure requirements.

There are no exceptions for church plans or government plans.

By Danielle Capilla, Originally Published By United Benefit Advisors

When it comes to Employee Assistance Programs, confidentiality is a concern for both employers and employees. As an employer, it is helpful to understand the terms and processes your EAP uses to keep information confidential and ensure that your employees and your workplace are safe.

When it comes to Employee Assistance Programs, confidentiality is a concern for both employers and employees. As an employer, it is helpful to understand the terms and processes your EAP uses to keep information confidential and ensure that your employees and your workplace are safe.