by admin | Jan 19, 2026 | Employee Benefits, Health Insurance

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) was signed into law on July 4, 2025, introducing significant updates to Health Savings Accounts (HSAs). Following this, the IRS released Notice 2026-5 to provide specific guidance on how these changes expand HSA eligibility and usage.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) was signed into law on July 4, 2025, introducing significant updates to Health Savings Accounts (HSAs). Following this, the IRS released Notice 2026-5 to provide specific guidance on how these changes expand HSA eligibility and usage.

The OBBBA broadens HSA availability through the following key provisions:

1. Permanent Telehealth Flexibility

The ability to receive telehealth and other remote care services before reaching the High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP) deductible has been made permanent. This ensures that individuals can access remote care without losing their HSA eligibility. This extension is effective for all plan years beginning after December 31, 2024.

2. Integration with Direct Primary Care (DPC)

The new law officially recognizes Direct Primary Care (DPC) arrangements as compatible with HSAs.

- Individuals in these arrangements can now contribute to an HSA.

- Periodic DPC fees are now classified as qualified medical expenses, meaning they can be paid for using tax-free HSA funds.

3. Expanded Plan Compatibility

Bronze and catastrophic plans offered through the ACA Exchange are now designated as HSA-compatible. This change applies regardless of whether these specific plans meet the traditional IRS requirements for an HDHP, significantly increasing the number of Americans eligible to open and fund an HSA.

Strategic Outlook for Employers

While some provisions are currently active, the majority of the OBBBA’s employee benefit changes will take full effect in 2026. Employers are encouraged to review these regulatory updates immediately to ensure benefit packages remain compliant and optimized for the coming year.

by admin | Jan 13, 2026 | Custom Content, Health Care Costs, Health Savings Account

A Health Savings Account (HSA) is a tax-advantaged savings account designed to help you pay for healthcare expenses. It offers valuable benefits now and in the future — from lowering your current healthcare costs to building long-term savings for retirement.

A Health Savings Account (HSA) is a tax-advantaged savings account designed to help you pay for healthcare expenses. It offers valuable benefits now and in the future — from lowering your current healthcare costs to building long-term savings for retirement.

- Understand the Basics

- Triple Tax Advantage: HSAs provide three powerful tax benefits — contributions are tax-deductible, growth is tax-deferred, and withdrawals for qualified medical expenses (QMEs) are completely tax-free.

- Eligibility: To open or contribute to an HSA, you must be enrolled in a high-deductible health plan (HDHP). These plans typically have higher deductibles and out-of-pocket costs but lower monthly premiums, allowing you to save more overall.

2026 Contribution Limits:

- Self-only coverage: $4,400

- Family coverage: $8,750

- Catch-up contribution (age 55+): $1,000

- Maximize Your Contributions

- Make regular contributions: Set up automatic transfers to your HSA to build your balance consistently.

- Take advantage of catch-up contributions: If you’re 55 or older, contribute an additional $1,000 annually to boost your savings.

- Use Your HSA Strategically

- Cover qualified medical expenses: Use HSA funds for expenses like doctor visits, prescriptions and over the counter medications, dental/vision care, hearing aids and other IRS-approved medical costs.

- Invest for long-term growth: Consider investing your HSA balance to grow tax-free over time. After age 65, you can make withdrawals for non-medical expenses without a penalty (though they’ll be taxed as regular income).

- Carry funds forward: Unlike Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs), HSA balances roll over year to year — your money stays with you even if you change jobs.

All HSA transactions must go toward Qualified Medical Expenses (QMEs) as defined by the IRS. You can review the full list of eligible expenses in the IRS Publication 502.

The Bottom Line

HSAs are among the most flexible and tax-efficient savings tools available. Because healthcare costs often rise with age, starting early and contributing consistently can significantly strengthen your financial security — both for medical needs and retirement. By understanding the basics of HSAs and following these tips, you can make the most out of this valuable financial tool.

by admin | Jan 5, 2026 | Custom Content, Employee Benefits

In our increasingly busy world, employee expectations are accelerating faster than ever before. A five-year-old benefits strategy simply cannot meet the complex, constant pressures workers face in 2026—be it financial stress, burnout, or caregiving responsibilities. The modern workforce is rejecting generic menus in favor of flexibility, strong financial support, and wellness options that align with their personal lives.

In our increasingly busy world, employee expectations are accelerating faster than ever before. A five-year-old benefits strategy simply cannot meet the complex, constant pressures workers face in 2026—be it financial stress, burnout, or caregiving responsibilities. The modern workforce is rejecting generic menus in favor of flexibility, strong financial support, and wellness options that align with their personal lives.

Employers face a critical challenge in 2026: balancing projected healthcare cost increases (around 10%) with the need to offer personalized, holistic, and competitive benefits.

Top 9 Trends Shaping 2026 Benefits Strategy:

- Managing Rising Healthcare Costs: Employers are adopting cost-management tactics — such as telemedicine, HSAs, and wellness incentives — to balance rising expenses driven by medical inflation, specialty drug use, and delayed care demand.

- Total Health and Well-Being:Benefits now integrate physical, mental, and financial wellness through EAPs, teletherapy, and wellness technology to promote holistic employee health.

- Women’s Health Expansion: Comprehensive care from fertility to menopause is becoming standard, improving retention, equity, and workforce engagement.

- Personalized Benefits Through AI:Technology enables tailored benefits selection, predictive analytics, and mobile access, meeting diverse employee needs.

- Mental Health Integration:Behavioral health is now fundamental, with digital tools, manager training, and open dialogue reducing stigma and driving productivity.

- Family and Caregiving Support:These benefits address the financial and emotional strain on the “sandwich generation” (caring for children and elders simultaneously). Expanded parental leave, dependent-care FSAs, and eldercare resources address pressures on multigenerational caregivers.

- Voluntary Benefits:Supplemental benefits provide a cost-effective way to offer additional value to employees. From pet insurance to identity theft protection, these benefits give employees the flexibility to select coverage that meets their individual needs.

- Financial Wellness and Retirement Security:Initiatives like 401(k) matching, financial counseling, and student-loan repayment reduce stress and strengthen financial stability.

- Upskilling and Development:Investing in employee growth as a key driver of retention and engagement, particularly among Gen Z and Millennials. Continuous learning opportunities, AI-driven training, and mentorship programs help attract and retain talent seeking career growth.

Ultimately, a strategic benefits plan that balances economic realities with genuine care for the workforce will be the decisive factor in attracting talent, boosting engagement, and building a resilient team ready for the year ahead.

by admin | Dec 28, 2025 | Compliance

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has issued Notice 2025-61, announcing a significant increase to the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) fee amount. Employers with self-insured health plans and health insurance issuers must take note of the new rate and upcoming compliance deadlines.

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has issued Notice 2025-61, announcing a significant increase to the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) fee amount. Employers with self-insured health plans and health insurance issuers must take note of the new rate and upcoming compliance deadlines.

What is the New PCORI Fee Amount?

The PCORI fee is increasing to $3.84 per covered life. This new rate applies to plan years that end on or after October 1, 2025, and before October 1, 2026.

For comparison, the previous fee amount (for plan years that ended on or after Oct. 1, 2024, and before Oct. 1, 2025) was $3.47 multiplied by the average number of lives covered under the plan.

Background and Applicability

The PCORI fee was originally established by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to fund comparative effectiveness research. Though initially set to expire in 2019, federal legislation extended the fee for an additional 10 years. The PCORI fee is now scheduled to apply through the plan or policy year ending before October 1, 2029.

The fee is imposed on:

- Health insurance issuers

- Sponsors of self-insured health plans

The fee is calculated based on the average number of covered lives under the plan, which generally includes employees, their enrolled spouses, and dependents (unless the plan is an HRA or FSA).

Reporting and Payment Deadlines

The PCORI fee must be reported and paid annually using IRS Form 720 (Quarterly Federal Excise Tax Return).

The fee is always due by July 31st of the year following the last day of the plan year.

Action for Self-Insured Plans: Employers with self-insured health plans should ensure they use the correct rate and meet the upcoming July 31st deadline corresponding to their plan year end.

Additional Resources:

PCORI Fee Overview Page

PCORI Fee FAQs

by admin | Dec 10, 2025 | Compliance, HIPAA

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has issued a final rule that requires covered entities—including many health plans—to update their Notice of Privacy Practices (Privacy Notice). This change enhances privacy protections for highly sensitive Substance Use Disorder (SUD) treatment records.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has issued a final rule that requires covered entities—including many health plans—to update their Notice of Privacy Practices (Privacy Notice). This change enhances privacy protections for highly sensitive Substance Use Disorder (SUD) treatment records.

Why the Update is Necessary

The HIPAA Privacy Rule already mandates that covered entities provide a Privacy Notice to explain how an individual’s Protected Health Information (PHI) is used.

However, the April 2024 final rule specifically addresses patient records involving SUD treatment from federally assisted programs (often referred to as “Part 2 programs”). Any covered entity that receives or maintains these Part 2 records must now update their Privacy Notice to reflect these additional, heightened protections.

The mandatory deadline for updating and distributing these notices is February 16, 2026.

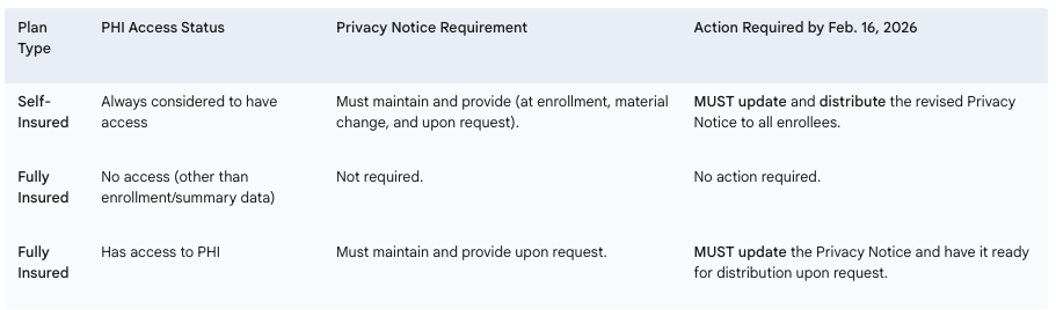

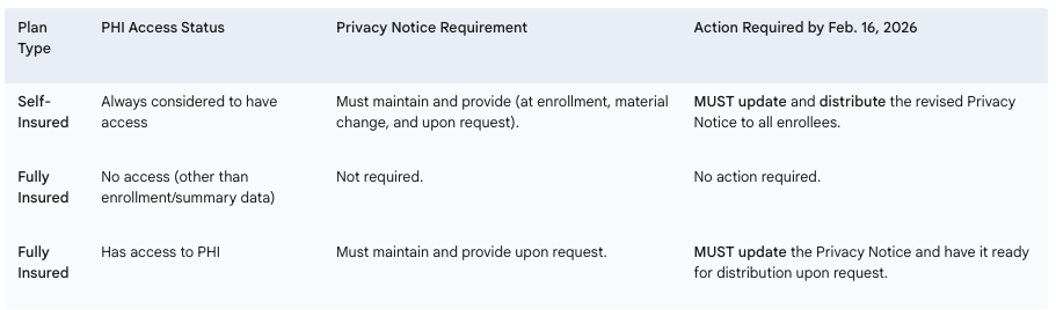

Required Employer Actions by Plan Type

Employers sponsoring health plans must determine their level of responsibility based on their plan’s funding structure and access to PHI.

Next Steps for Employers: Employers with self-insured health plans, or fully insured plans that manage PHI, must immediately begin the process of updating their Privacy Notices to incorporate the new requirements for SUD treatment records. It is currently uncertain if HHS will release updated model privacy notices before the deadline.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) was signed into law on July 4, 2025, introducing significant updates to Health Savings Accounts (HSAs). Following this, the IRS released Notice 2026-5 to provide specific guidance on how these changes expand HSA eligibility and usage.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) was signed into law on July 4, 2025, introducing significant updates to Health Savings Accounts (HSAs). Following this, the IRS released Notice 2026-5 to provide specific guidance on how these changes expand HSA eligibility and usage.