by admin | May 30, 2023 | Employee Benefits, HSA/HRA

Are you the type of person who loves to save money? You’ll be happy to know that there’s a way to do so with your health care costs. It starts with medical expense accounts which let you set aside money to pay for certain health products and services. One type of medical expense account is a Health Savings Account (HSA).

Are you the type of person who loves to save money? You’ll be happy to know that there’s a way to do so with your health care costs. It starts with medical expense accounts which let you set aside money to pay for certain health products and services. One type of medical expense account is a Health Savings Account (HSA).

How Does An HSA Work?

An HSA is a type of personal savings account you can use to pay certain health care costs. An HSA lets you pay for qualified health, dental and vision care costs for yourself, spouse and dependents with tax-free money. The money you contribute comes out of your paycheck – before taxes – and that is how you save to pay for your out-of-pocket health care expenses. Like a regular savings account, your HSA has an interest rate that allows your money to grow while sitting in the account. Your employer also has the option of contributing to your HSA, helping it to grow faster.

If you don’t use all of your HSA funds during the calendar year, you can roll that money over. An HSA is owned by you so you take it with you no matter if you change plans, change jobs or if you decide to retire. You will get a debit card which is linked to your HSA when you set up your account that you use to pay for eligible expenses.

You must be enrolled in a High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP) to open and contribute to an HSA. HDHPs medical plans aim to minimize your health care costs if you don’t use your plan a lot but keep you financially protected in cases of illness or emergency. Similar to a car insurance policy, you pay for your expenses up to the point that you meet your deductible and then the insurance coverage begins. The higher the deductible you choose, the smaller the monthly cost will be. But it also means that when you have health expenses, you are responsible for all of the costs up to your deductible amount. Rather than pay for your health expenses that occur before hitting your deductible out of your pocket, you can pay for those expenses using pre-tax dollars from your HSA account.

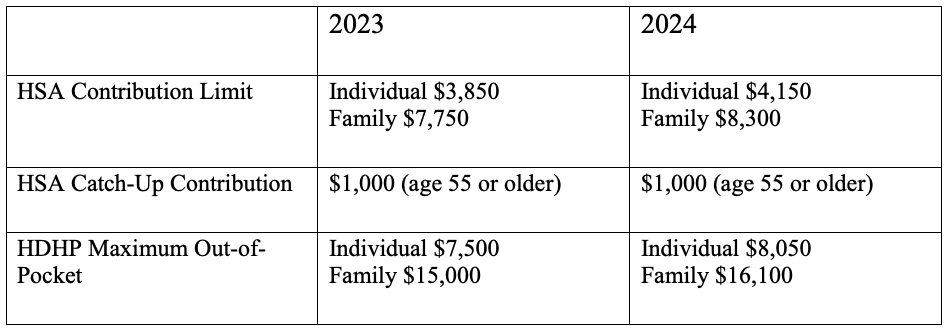

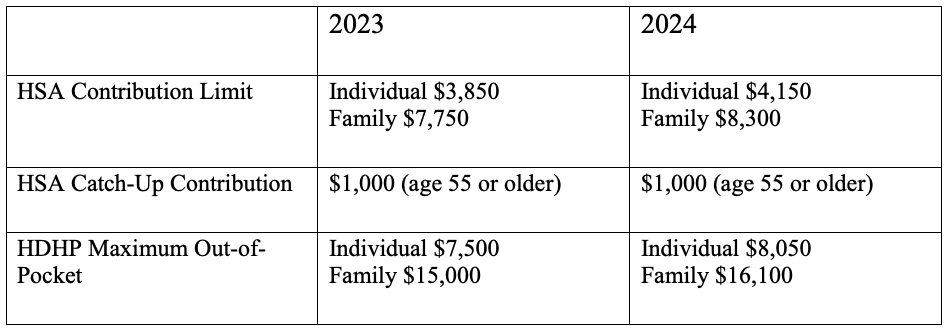

Federal law includes strict guidelines for HSAs including HDHP cost sharing and annual limits on contributions. The amount you contribute can be adjusted throughout the year but they do have an annual limit on how much you can contribute per year. This limit is set by the IRS and usually increases each year. Contribution limits for 2023 and 2024 are:

What Are the Benefits of Having an HSA?

- Money goes in tax-free – Your HSA contributions are made on a pre-tax basis and are also tax deductible

- Money comes out tax-free – Eligible healthcare purchases can be made directly from the HSA account

- Earn interest, tax-free – The interest on HSA funds grows on a tax-free basis. Unlike most savings accounts, interest earned on an HSA is not considered taxable income when funds are used for eligible medical expenses.

- Your HSA balance can be invested – Depending on your HSA, you may be eligible to invest your HSA similar to a 401k or IRA – in an interest-bearing account, mutual fund, stocks or bonds.

- Your HSA balance can be carried over – Unlike a Flexible Spending Account (FSA), an HSA is not a use-it-or-lose-it account. You can carry over your balance year after year.

- You can use your HSA to add to your retirement funds – After the age of 65, you can withdraw funds from your HSA for any reason without penalty.

The Bottom Line

HSAs are often referred to as triple tax-advantaged and are one of the best savings and investment tools available under the U.S. tax code. As a person ages, medical expenses tend to increase, particularly when reaching retirement age and beyond. Therefore, starting an HSA early and allowing it to accumulate over a long period, can contribute greatly to securing your financial future.

by admin | May 23, 2023 | Compliance

2024 BENEFIT PARAMETERS FOR MEDICARE PART D CREDITABLE COVERAGE DISCLOSURES ANNOUNCED

2024 BENEFIT PARAMETERS FOR MEDICARE PART D CREDITABLE COVERAGE DISCLOSURES ANNOUNCED

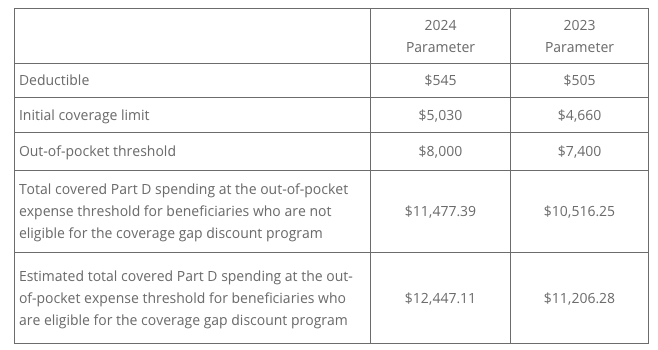

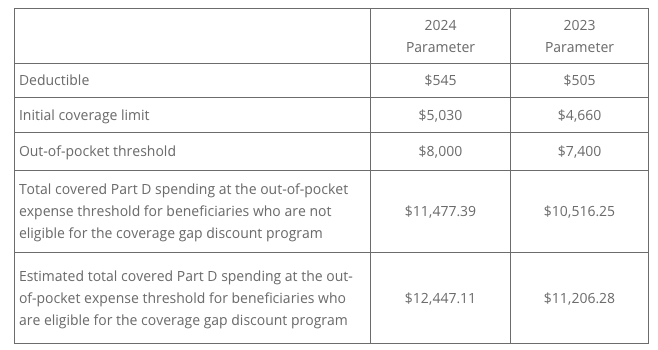

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released a Fact Sheet announcing the 2024 benefit parameters for Medicare Part D. These factors are used to determine the actuarial value of defined standard Medicare Part D coverage under CMS guidelines.

Each year, Medicare Part D requires that employers offering prescription drug coverage to Part D eligible individuals (including active or disabled employees, retirees, COBRA participants, and beneficiaries) disclose to those individuals and CMS whether the prescription plan coverage offered is creditable or non-creditable. Creditable coverage meets or exceeds the value of defined standard Medicare Part D coverage.

Insurance carriers and providers of the prescription benefit will typically notify the plan sponsor if their prescription plan is creditable or non-creditable. The 2024 parameters for Medicare Part D are:

The Online Disclosure to CMS Form must be submitted to CMS annually, and upon any change that affects whether the drug coverage is creditable:

- Within 60 days after the beginning date of the plan year

- Within 30 days after the termination of the prescription drug plan

- Within 30 days after any change in the creditable coverage status of the prescription drug plan

QUESTION OF THE MONTH

Q: Where can I find the updated RxDC reporting instructions?

A: The most recent version of the reporting instructions and templates can be found on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid website.

To receive an email when the instructions are updated, create a Registration for Technical Assistance Portal (REGTAP) account. Select the checkbox “Please send me updates for the Consolidated Appropriations Act / No Surprises Act” in your account settings.

© UBA. All rights reserved.

| This information is general in nature and provided for educational purposes only. It is not intended to provide legal advice. You should not act on this information without consulting legal counsel or other knowledgeable advisors. |

by admin | May 16, 2023 | Health Insurance, Hot Topics

Healthcare costs, and consequently employee health benefit costs, have been growing at an alarming rate in recent years. The U.S. as a nation spends more on health care than any other developed country but has worse health outcomes. How is this possible?

Healthcare costs, and consequently employee health benefit costs, have been growing at an alarming rate in recent years. The U.S. as a nation spends more on health care than any other developed country but has worse health outcomes. How is this possible?

Four Key Factors Driving U.S. Healthcare Costs:

Healthcare gets more expensive when the population expands, as people get older and live longer. The Baby Boomers, one of America’s largest adult generations, is approaching retirement age. Because of this, the 65+ population is growing at an unprecedented rate. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 21% of the entire population will be age 65 or older by 2030. Older Americans will make up almost one-quarter of the population by 2060.

This growth is likely to contribute to rising healthcare costs in two important ways:

- Growth in Medicare enrollment

- More complex, chronic conditions

- U.S. Population Is Growing More Unhealthy

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 6 out of every 10 adults in the U.S. have at least one chronic disease, such as asthma, heart disease, high blood pressure, or diabetes, which all drive up health insurance costs. In 2020, the health care costs of people with at least one chronic condition were responsible for 86% of health care spending.

Additionally, recent data finds that nearly 20% of children and 40% of adults over 20 in the U.S. are either overweight or obese, which can lead to chronic diseases and inflated healthcare spending.

On average, Americans shell out almost twice as much for pharmaceutical drugs as citizens of other industrialized countries pay. Moreover, prescription drug spending in the U.S. will grow by 6.1% each year through 2027, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) estimates.

Drug pricing strategies also contribute to rising healthcare costs. Drug manufacturers establish a list price based on their product’s estimated value, and manufacturers can raise this list price as they see fit. In the United States, there are few regulations to prevent manufacturers from inflating drug prices in this way.

Simply put, multiple systems create waste. “Administrative” costs are frequently cited as a cause for excess medical spending. The U.S. spends about 8% of its health care dollar on administrative costs, compared to 1% to 3% in the 10 other countries the JAMA study looked at.

Why is administrative spending so high in the United States? The U.S. operates within a complex, multi-payor system, in which healthcare costs are financed by many different payors. With so many stakeholders involved, healthcare administration becomes a complicated, inefficient process.

These inefficiencies contribute to excess administrative spending. The main component of excess administrative spending is billing and insurance-related (BIR) costs. These are overhead costs related to medical billing, and include services like claims submission, claims reconciliation and payment processing.

Administrative costs, an aging population, rising prescription drug costs, and lifestyle choices all play a factor in ballooning healthcare expenses. While some of these factors are not in your control, others are. Find out where you can make a difference, not only in health insurance costs, but also to your overall health!

by admin | May 9, 2023 | Johnson & Dugan News

Volunteers make an immeasurable difference in people’s lives and often serve with the intention of helping others. But, did you know that volunteering can benefit your mental health as well?

Volunteers make an immeasurable difference in people’s lives and often serve with the intention of helping others. But, did you know that volunteering can benefit your mental health as well?

While it’s true that the more you volunteer, the more benefits you’ll experience, volunteering doesn’t have to involve a long-term commitment or take a huge amount of time out of your busy day. Donating your time in even simple ways can help those in need and improve your health and happiness.

Here are a few of the mental health benefits that result from volunteering:

- Improves Mental and Physical Health – Volunteer activities keep people moving and thinking at the same time. Additionally, volunteering reduces stress and increases positive, relaxed feelings by releasing dopamine. By spending time in service to others, volunteers report feeling a sense of meaning and appreciation, both given and received, which can have a stress-reducing effect. Reduced stress further decreases risk of many physical and mental health problems, such as heart disease, stroke, depression, anxiety and general illness.

- Provides a Sense of Purpose – Volunteering connects you with a cause bigger than yourself. Many individuals feel that where they volunteer says something about who they are. Dedicating time to a cause can give you new direction and allow you to find meaning in something unexpected. It can also take your mind off your own troubles while keeping you mentally stimulated.

- Nurtures New and Existing Relationships – Loneliness has been described as an epidemic in the U.S. and making friends as an adult can be difficult. Volunteering is a remedy to this problem because it increases social interactions and builds a support system based on shared interests. Like-minded, like-hearted people come together over common values. Whether it is campaigning for specific political goals, volunteering time to help sick children in the hospital or working in a soup kitchen, a volunteer activity can help break the ice with potential new friends all while giving back to your community.

- Increases Confidence – Some volunteering activities require learning new skills. Being in an unfamiliar environment while gaining a new skill provides mental stimulation. Additionally, while growing your skill set to make a difference for others, you gain a sense of pride which can lead to having a more positive view of yourself.

- Ignites Passion – Volunteering is a fun way to explore different interests and learn from others. It can be an energizing escape from your daily routine – especially if you work in front of a computer all day in an office and long to be more active outdoors. You can look for opportunities to help with walking dogs at your local animal shelter or help with building homes for those in need.

- Makes You Happy – Research shows that brain activity spikes during volunteer activities. We are social animals and are designed to be part of a wider community. Volunteering helps you make the world a better place and helping others provides great pleasure.

What are you passionate about?

Do you want to feel good while doing good?

How would you like to see the world be a better place?

There’s a volunteer activity perfect for your skill set and time availability. Churches, schools, or libraries can always use your support. Whether it’s tutoring a student, visiting the elderly, caring for abandoned animals, or being a baby cuddler (yes – that’s holding babies in the neonatal intensive care unit in the hospitals!), the possibilities are endless. There are even ways to volunteer remotely via phone or computer. Getting involved will boost your well-being while you are making a difference in the community.

by admin | May 4, 2023 | Human Resources

The biggest challenge to employee engagement is burnout, according to the more than 400 respondents to the HR Exchange Network State of HR survey. Burnout, with 23% of the vote, was the top concern for motivating employees.

The biggest challenge to employee engagement is burnout, according to the more than 400 respondents to the HR Exchange Network State of HR survey. Burnout, with 23% of the vote, was the top concern for motivating employees.

WHAT IS BURNOUT?

Burnout is a psychological syndrome emerging as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job, according to the National Institutes of Health. The three key dimensions of this response are an overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.

Knowing this definition of burnout makes the second biggest challenge to employee engagement all the more interesting. In the same State of HR survey, 20% of respondents said the blurring of work and life was the biggest threat to employee engagement.

Clearly, HR professionals are aware that people feel overworked and overburdened by their job. More than 75% of surveyed HR leaders reported an increase in employees identifying as being burned out, which was up from 42% in September 2020, according to a Conference Board survey in 2022.

Although the concept of burnout dates back to the 1970s, the World Health Organization (WHO) only first recognized burnout as an occupational phenomenon in its Revision of the Classification of Diseases in 2019. This led the WHO developing suggestions for workplace well-being, which HR Exchange Network recently outlined for readers.

WHAT SHOULD HR DO ABOUT BURNOUT?

Judging from the State of HR responses, addressing burnout is vital to any effective employee engagement strategy. The problem is that the same survey showed that HR professionals are concerned about the possibiity of recession, budget cuts, and other consequences requiring they do more with less. This economic downturn makes the workplace ripe for burnout.

Still, prioritizing mental health and wellness is evident in the survey responses, too. While 55% of respondents said medical, dental, and vision insurance was the top benefit being offered or under consideration, wellness programs (53%), employee assistance programs (45%), and mental health coaching (38%) came in second, third, and fourth place on that list.

Also, 22% of respondents to the State of HR survey said retaining top talent was the biggest challenge they faced as they confront the future of work. In other words, keeping people healthy and at the company is of the utmost importance at a time when demographic shifts are causing a labor shortage, companies are laying off some workers, and everyone is grappling with the arrival of advanced artificial intelligence that is transforming the workplace.

Indeed, Human Resources professionals and employers are recognizing that mental health and wellness of employees directly relates to their success, engagement, and retention. As HR creates human-centric organizations that rely on people first to carry out the vision of an organization’s leaders, it must contend with the fact that humans must be healthy to perform to their full potential. While burnout is happening just about everywhere, HR is taking on the burden of fighting it. In fact, it’s a matter of aligning business objectives with talent management.

By Francesca DiMeglio

Originally posted on HR Exchange Network

The biggest challenge to employee engagement is burnout, according to the more than 400 respondents to the HR Exchange Network State of HR survey. Burnout, with 23% of the vote, was the top concern for motivating employees.

The biggest challenge to employee engagement is burnout, according to the more than 400 respondents to the HR Exchange Network State of HR survey. Burnout, with 23% of the vote, was the top concern for motivating employees.